Leonardo Da Vinci by Walter Isaacson Is a Hardy Meal of Knowledge for Pondering the Human Condition

So here we have this dude Leo — illegitimate, barely formally educated, who would likely be diagnosed with (at least) ADD today —whom the world has almost unanimously enthroned as one of its greatest artistic and scientific geniuses.

This is a book about scandalous and wonderful times, not unlike today, and about one powerfully creative and observant soul in their midst.

One may chalk off Leonardo Da Vinci by Walter Isaacson as fodder for fanboys of academia and modern renaissance men wannabes. And in some ways they’d be right.

However, considering the scope of the ground Isaacson covers, the book shines in its ability to remain cohesive.

Though the primary focus is on Leonardo’s life and work, there is a ton of peripheral information within its nearly 600 pages — including notes and other resources, which stand alone as an intellectual treasure trove.

In addition to the obvious Leo bio, we get scoops of:

- art history

- art theory

- history

- military history

- medical history

And probably other categories I’ve missed.

With Isaacson at the helm, we are presented with a Swiss Army knife of narrative nonfiction.

While writing the book, Isaacson immersed himself in Leonardo’s works, comprised of paintings and over 7,200 pages of notebook entries¹ — which include drawings and writings. The result is a deep dive into Leo’s life and work, one that interweaves the artist’s own thoughts and those of various scholars and art experts. We get to know Leonardo, not as perfect, but as flawed, with a remarkable ability to maintain a childlike fascination.

If you’re trying to understand the world a little better, especially the western part — this book is a worthwhile investment.

Now, travel with me as I distill my thoughts on the book and what stuck with me.

Book details & binding woes

A heaping helping of color images makes the book visually appealing.

Within the first few pages, we are presented with a multi-page timeline detailing big moments of Leonardo’s life. Throughout the rest of the book, Isaacson uses other images, primarily of Leonardo’s works, to augment and support his narrative.

While the softcover version is printed using decent paper, the hardcover version is printed using high-quality — 80-weight, I believe — glossy paper, which makes the visuals and text pop.

Annoyingly, I only know about those differences because my first copy, a used hardcover, had its binding fail halfway through reading it.

All the pages up to the one I was reading became detached from the binding. And each new one I flipped over did the same. With my notes piling up in the detached pages, the increasingly dismembered book was more valuable to me than what I had paid for it.

In my search for an easy way to fix the binding, I came across product reviews where others had similar issues, including one that recommended opting for the softcover version to avoid the problem.

So, I nabbed one of those, deciphered the remainder of the book (with no clear signs of cleavage), and begrudgingly copied over my marginalia.

The hardcover is really nice, and the majority of its reviews are positive, with no mention of binding issues. But there’s a slight possibility the binding will fail.

Despite his genius, Leonardo was human

He was born out of wedlock.

In Childhood (chapter 1), we learn Leonardo was a lovechild. His parents — a wealthy, well-connected notary and an impoverished orphan girl — were never married.

We also hear from the 19th-century Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt (1818–1897), who Isaacson uses as a reference, that Renaissance Italy was “a golden age for bastards.”

Isaacson explains:

“Especially among the ruling and aristocratic classes, being illegitimate was no hindrance. … Illegitimacy freed some imaginative and free-spirited young men to be creative at a time when [it] was increasingly rewarded.”

Isaacson’s perspective is down-to-earth, understanding, and insightful.

He makes the point that, if Leonardo had been legitimate, he would have been pressured to be a notary — the vocation of his dad. Not only would Leo have made a lousy notary, but the world would have missed out on his genius.

He had little formal education.

Isaacson relays that, “other than a little training in commercial math at what was known as an ‘abacus school,’ Leonardo was mainly self-taught.”

He once signed his name:

“Leonardo da Vinci, disscepolo della sperientia,”

The latter portion translates to “disciple of experience.”

According to Isaacson, Leonardo had a “lack of reverence for authority” and a “willingness to challenge received wisdom,” which led him to develop his own methods of observing and understanding nature — these “foreshadowed” the scientific method.

That said, he embraced “book learning” and studied widely — inevitably finding balance between experience and embracing the knowledge of others.

He had a reputation for leaving work unfinished.

At times he quit projects because he couldn’t satisfy his own perfectionism, and at others, he simply lost interest, likely because another project caught his eye.

When Leonardo was painting the Last Supper at Santa Maria delle Grazie², he might sit for hours one day looking at his unfinished work. On another, he might spend the whole day painting, or he might rush into the hall at midday, apply a few brush strokes, and then quickly disappear.

Only Leonardo knew when he came and went or when he worked or rested.

Expecting Leonardo to operate like any other worker, the church prior complained to the Duke of Milan:

“When Leonardo was summoned by the duke, they ended up having a discussion about how creativity occurs. Sometimes it requires going slowly, pausing, even procrastinating. That allows ideas to marinate, Leonardo explained. Intuition needs nurturing.”

Since I’m a distractable creative myself, knowing this detail about Leo is reassuring.

It’s easy for creatives to beat themselves up for not operating like they’re on an assembly line, but — at least in my own experience — working that way all the time doesn’t lead to the best results. What comes out is stiff and dull.

To counterbalance Leo’s unstructured approach to work, in a “how to be like Leo” section — starting on page 519 — Isaacson refers to Steve Jobs.

Like Leonardo, Steve was a perfectionist.

For example, in 1983, he postponed the launch of the original Macintosh to redesign the internal components to be more elegant. Yet, as Isaacson tells us, Steve also said “Real artist’s ship.” around the same time.

For creatives, balancing those two perspectives — the need to nurture creative vision and the need to deliver — is a fundamental aspect of a successful career.

I don’t think anyone ever said getting it right was easy.

A bit of art instruction and art history

If you’re interested in art, either creating it or enjoying it, this book doubles as a basic art history and art technique survey.

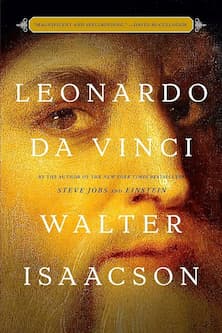

Isaacson touches on all of Leonardo’s major paintings — and even some by Michelangelo and other artists. We are given insight into the history of art as well as what the art community was like during Leonardo’s time.

Using an image as a guide, Isaacson will often give a detailed analysis of Leonardo’s techniques and methods. With my subpar knowledge of the art world, I found these forays interesting.

We get insight into subjects like perspective, color theory, and optics — often through direct quotations of Leonardo’s written work.

Thus, in many places, we get to learn about painting, through this book, from Leonardo himself — and I think that’s pretty cool.

Here are a few examples of Leonardo’s instructional passages:

“The first intention of the painter … is to make a flat surface display a body as if modeled and separated from this plane, and he who surpasses others in this skill deserves most praise. This accomplishment, with which the science of painting is crowned, arises from light and shade, or we may say chiaroscuro [formed from the Italian words chiaro(light) and scuro(dark)].”

“There are three branches of perspective,” [Leonardo] wrote. “The first deals with the apparent diminution [or decreasing in size] of objects as they recede from the eye. … The second addresses the way colors vary as they recede from the eye. The third is concerned with how the objects in a picture ought to be to be less detailed as they become more remote.”

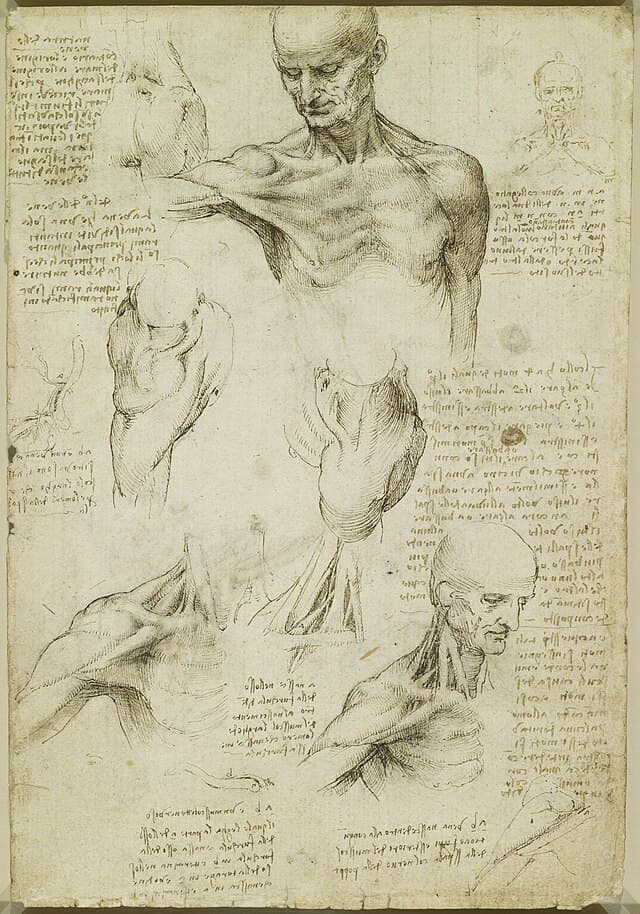

“It is necessary for the painter, in order to be good at arranging the parts of the body in attitudes and gestures which can be represented in the nude, to know the anatomy of the sinews, bones and muscles and tendons.”

A bit of history

We get to go back to the peak of the Italian Renaissance and the time period of Leonardo’s life (1452–1519).

We learn of the politics of the day, as well as the regional struggles for power. We see how Leonardo lived through turbulent times. Contrary to what I’ve always assumed, for a period of artistic and scientific expansion.

Isaacson shows us that Leonardo was connected to many other historical figures, such as:

- Michelangelo

- Niccolò Machiavelli

- Cesare Borgia

- Agostino Vespucci (Amerigo Vespucci’s cousin)

- Lorenzo de’ Medici

- Ludovico Sforza

- Francis I, the King of France

I didn’t know Michelangelo was a hothead and a rival of Leonardo.

Hell, I didn’t even know that they were alive at the same time. And I always assumed Michelangelo was the laid-back type — the stereotypical artist. But nope, that’s not what we see in Michelangelo and the Lost Battles (chapter 25), which is largely devoted to a brief, turbulent, and fascinating overlap in their careers.

Around 1502–1503, Leonardo spent time with Machiavelli while they were both employed by Cesare Borgia.

Borgia was a leader known for being ruthless; he was the subject of Machiavelli’s famous book, The Prince. On August 18, 1502, Cesare wrote a dispatch that said Leonardo was a “well-beloved family friend” as well as “[an] architect and [the] engineer general.” Isaacson gives us the full text of the dispatch — one of many other textual historical artifacts throughout the book — in Cesare Borgia (chapter 23).

A bit of military history

Though he tinkered with military engineering, Leonardo’s quest for knowledge and his skills allowed him to avoid becoming overly entangled in politics and war. He held value to leaders like Ludovico Sforza and Cesare Borgia because of his skill in engineering and his ability to entertain as an impresario³.

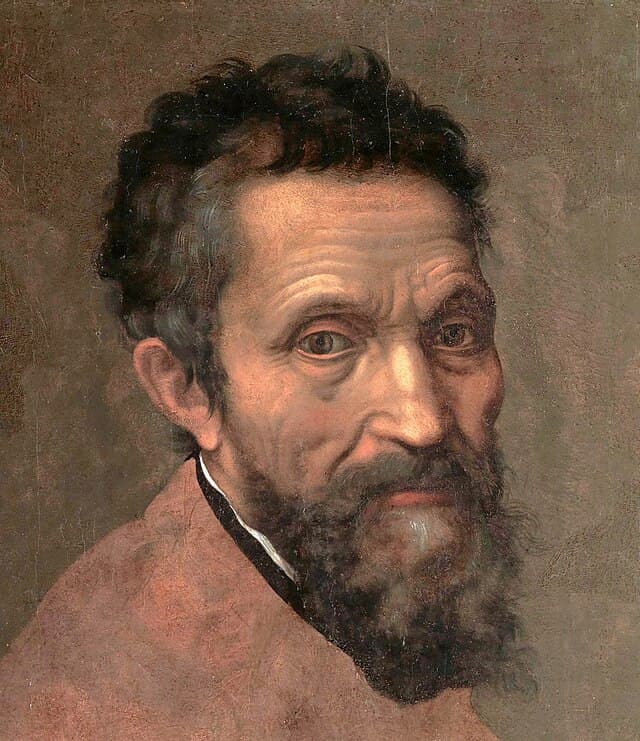

While employed by Cesare Borgia, Leonardo lived in Imola, in northern Italy — a key stronghold at the time. Leonardo used innovative techniques to make a map (fig. 87) of the city that was “accurate, detailed, and easily read[able].” The map was of great tactical use, as commanders could use it to plan troop movements, siege tactics, and defensive positions and reinforcements.

And it’s just one example of several contributions Leonardo made to military history.

Another area that Isaacson covers — which sticks out to me — is Leonardo’s contributions to castle building, but I can’t give away all the good stuff.

A bit of medical history

Throughout the book, Isaacson covers a lot of ground involving Leonardo’s contribution to medical history.

According to Isaacson, Leonardo was largely underappreciated for finding new ways to present information visually. As he did with cartography when he created the map of Imola, Leonardo also pushed anatomy forward.

“…[H]e drew muscles, blood, bones, organs, and blood vessels from different angles, and he pioneered the method of depicting them in multiple layers, like the transparencies of body layers found in encyclopedias centuries later.”

The drawings that Leonardo created were the “first of their kind.” To create them, Leonardo performed at least 30 autopsies. Isaacson delves deeply into this period of Leonardo’s life as well as his other medical discoveries in Anatomy, Round Two (chapter 27).

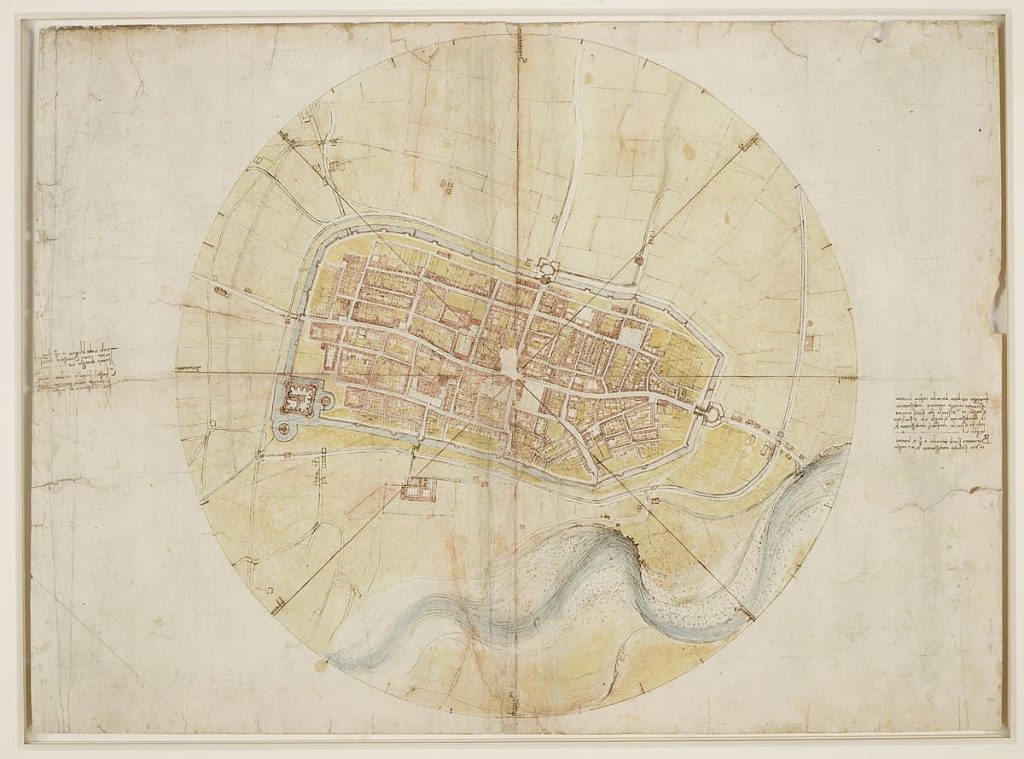

La Bella Principessa & the “Leo biz”

In the last section of The Milan Portraits (chapter 16) Isaacson brings us up to speed on the controversy surrounding “La Bella Principessa,” a painting that holds a contentious place in the art world and has since the late 1990s.

Isaacson’s thorough explanation reads like something out of a movie.

In short, some experts say it is a painting by Leo and have presented some evidence in support of that possibility, while other experts say it’s not and have harsh criticism and the weight of their vocational positions to prove it.

So everyone else is stuck flipping a coin.

That said — when I look at the painting, with my peasant eyes — I find it quite captivating… so there’s that.

While Isaacson uses about 10 pages to walk through the situation, a rough outline of the “Leonardo Business” also becomes clear. It comprises scholars, art collectors, and various other classes of Leo minions.

This all made me think of humanity’s habit of idolizing people. As interesting as the lives and work of others can be, it’s easy to get lost in them. I think — or hope — Leonardo would agree with me here… it’s important to focus on your own path.

My final thoughts

At times, I found Isaacson’s pacing to be somewhat offbeat.

His interweaving of Leonardo’s personal life, the technical details of his projects, and the sociopolitical environment around him was sometimes unpredictable.

After a section on Leonardo’s personal life, I would be hooked. I’d want to hear more of the same, only to be brought into a deep dive of a piece of Leonardo’s work — a who’s who of each brush stroke and pen line.

But I guess that’s the nature of a book like this — it’s not called “Leo’s Personal Life.”

Isaacson had a lot of ground to cover. Besides, it can be argued that the technical offerings — providing so much detail into how this genius’s mind worked — give us a more profound look at his personal side.

Ultimately, Isaacson keeps the tension and keeps us coming back for more.

I concede.

We can all learn from Leonardo’s creative purity.

Leonardo Da Vinci made little effort to publish the vast majority of his work.

He sought knowledge and creative expansion for their own sake. And the purity with which it was pursued — without extreme political and economic influence — is why it has proven useful. Maybe today’s creatives, myself included — in their mad rush to release their work to the world — could benefit from Leonardo’s languid approach to work.

Though Leo was a hard worker, he didn’t like to rush.

Many of us are so concerned with rapid production and growing an audience that we fail to serve our own souls. We fail to produce adequate earthbound representations of our visions and intellectual discoveries. We break under the pressure of a world that, at first glance, doesn’t seem to appreciate us unless we pretend to be this week’s flavor.

That farce is reinforced and taken advantage of by the many self-appointed gatekeepers of a limitless space that’s free to all. Through them, we’re taught to cheat in whatever way we can.

And, if we take their bait, we lose our real value… our love of exploration.

Footnotes

¹ Leonardo da Vinci’s handwritten notebooks (often referred to as “codexes”) span anatomy, engineering, astronomy, art, and natural science. These manuscripts showcase his “mirror-script” writing, intricate sketches, and relentless curiosity.

² Santa Maria delle Grazie is a historic church and Dominican convent in Milan, Italy. It is known for housing Leonardo da Vinci’s painting The Last Supper, which Isaacson dedicates chapter 18 of the book to. The church is open to visitors.

³ An impresario is a master (or organizer) of events. Isaacson covers this aspect of Leo’s life heavily in Court Entertainer (chapter 6).