“

Many of us don’t know how to sit still.

Without a steady stream of stimuli we become bored, anxious, or even afraid. We’ve learned to keep our minds incessantly busy. By doing so, we avoid discomfort and the work that comes with answering the big questions about life — the type that come up when we allow our minds to slow down.

By avoiding silence, we keep things light and easy.

At least that’s what we tell ourselves.

But there’s a cost to not exploring our inner world.

Boredom and “Brain Modes”

There’s research showing that the sensation of boredom is associated with the activation of a system of interconnected regions in our brain called the Default Mode Network (DMN).

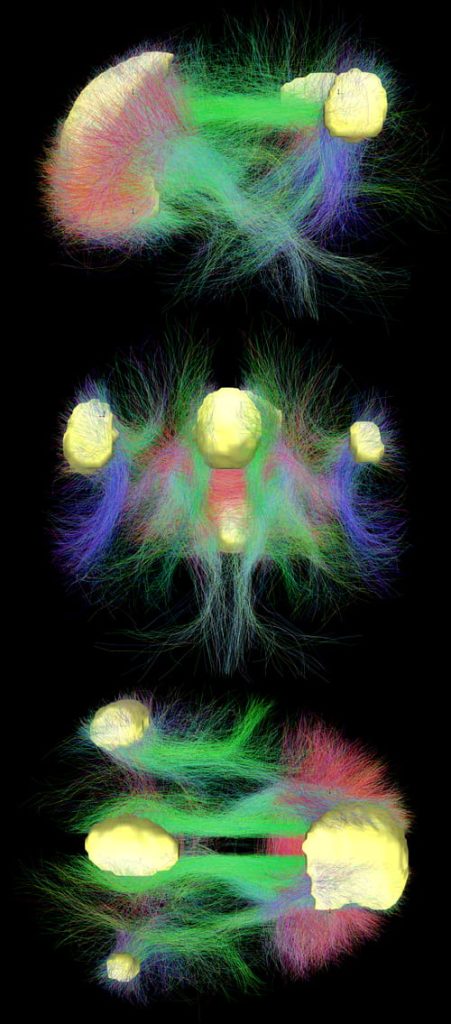

The interesting image below shows the main regions of the DMN in yellow, and the flow of connectivity between the regions in red, green, and blue.

The DMN is most active when we’re inwardly focused. Contrarily, when we are externally focused (working, watching television, etc.), the DMN is dormant, and two other brain regions are active instead. Those two regions are known in simplistic terms as the Attention Networks (AN) and the Control Networks (CN).

I won’t be going into the scientific complexities of these regions — I’m not qualified to. In short, they perform activities related to what their names suggest. The AN manages how we focus, while the CN is responsible for higher-order decision-making.

As a person’s focus wanes, the Attention and Control Networks become less active and the DMN starts to activate.

Once the DMN is active, a person might:

- Self-reflect or think about their own personality and emotions.

- Remember things that happened in the past.

- Contemplate what might happen in the future.

- Contemplate what other people are thinking or feeling.

- Daydream or think more abstractly than usual.

Thus boredom is natural: a transition period between our outer and inner worlds. Perhaps this is why boredom can feel so uncomfortable… our brain is changing operating modes.

The Brain’s Janitorial System

From my perspective, the Default Mode Network is part of a cleansing and organizing process that turns on whenever it gets the chance — when we stop consciously focusing our attention on external stimuli.

Meditation is a big part of my life, so I am keenly aware of how the mind becomes restless at the beginning of a session.

As we begin sitting in silence, all the things we haven’t dealt with start coming up.

Our mind is asking the question: “What should we do about this?”

Our mind wants answers, and I’ll touch on how we might deal with this in the next section.

Eventually, the DMN starts to calm down. At the same time, other brain regions activate, especially those related to attention, sensory input, and interoception — a term that means awareness of signals coming from inside the body, such as breathing, heartbeat, and emotions.

It’s at this time that the experience of meditation begins. Mental chatter subsides, and our perception heightens. We become deeply aware of the present moment. We move from thinking about experiencing to actually experiencing.

The more we spend time in this state, the more likely we are to experience it when we’re not sitting to meditate. In this way, meditation leads to deeper presence in all areas of life.

Practical Implications

To quickly summarize, there are 2 main transitions that I’ve covered:

- The brain’s transition from an externally focused state to an internally focused state. The Attention and Control networks become less active, while the Default Mode Network begins to ramp up in activity — often bringing up contemplative thoughts, fears, anxieties, etc.

- The brain’s transition from the Default Mode Network to a calm state of enhanced awareness. The DMN becomes less active, while other networks, related to attention, and sensory and bodily awareness, become more active — mental chatter lessens, and we often become deeply aware of the present moment.

From my experience, we can speed up the process of getting from point A (an overactive mind) to point B (deep presence), through preparing ourselves in advance.

Since we know that as the DMN activates all sorts of thoughts — about our past, our future, our dreams, our fears, and so on — are going to come up, we can work through some of this beforehand.

More specifically, we can organize our mind before we sit to meditate, just like warming up before a workout.

In my case, this usually means that I:

- Create a mind map.

- Write a to-do list.

- Do a “negativity burn”.

I may do all these things, or just one of them. It really depends on what’s going on at the time.

- If I’m anxious and uncertain what to do next, I’ll mind map.

- If I know I need to get a lot done one day, I’ll do a to-do list.

- If I’m angry or thinking negatively, I’ll do a negativity burn.

If I do all three in this order: negativity burn, to-do list, and then mind map, I usually feel pretty clear-headed afterward, and ready to sit in silence, feeling less burdened.

But whatever I do, the goal is the same: to speed up the process of sorting through what’s going to come up when I start sitting in silence.

When we’re used to a busy life, sitting in silence can be difficult.

It takes time and consistency to sort through the muck that comes up. But over time, things start clearing up. And that clarity translates into other areas of life.

The silence gives us access to new perspectives about our thoughts and our place in life — we gain a bird’s eye view.

In practical terms, it enables us to make life decisions that many never muster up the courage to make.

We become wiser as we sort out the undercurrents of our psyche. We get a greater handle on who we are and what makes us tick. And, in some ways, we understand others a little better also.

These changes can be slow, but slow change is stable change.